THE TENNESSEE STATE HALL OF FAME

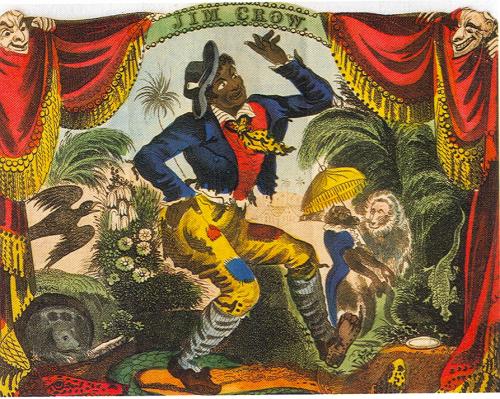

With the end of slavery and the developments of Reconstruction, blacks gained significant new rights, but following Reconstruction they saw their recently won rights erode under the force of “Jim Crow” laws. The term “Jim Crow” came from an 1820s comical dance tune called “Jump Jim Crow” that poked fun at blacks.

These laws required public schools and all public accommodations to be segregated. Such laws forced blacks to acknowledge publicly a lower racial status. The late 1880s saw Democrats once again take power in state government, and they proceeded to minimize if not eliminate black political influence in the state by introducing a poll tax and voter literacy requirements. These laws effectively disfranchised blacks until after World War II. In 1896, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled, in Plessy vs. Ferguson, that “separate but equal” laws were constitutional. In fact, equality was rarely the case. Black Tennesseans resisted such laws and social practices, but violence (most notably lynchings) kept blacks “in their place.” It is true that segregation fostered the growth of a black middle class by keeping them isolated in their own communities. Businessmen, ministers and professionals emerged to serve the needs of the people in these segregated communities. In spite of conditions, some blacks won political offices. Sampson W. Keeble, a barber from Nashville, was the first black elected to the Tennessee General Assembly in 1872 (during Reconstruction). In the 1880s, black Republicans in West Tennessee sent black representatives to the state legislature, and J.H.M Graham, a black editor from Clarksville, was elected to the state legislature in 1896.

The period encompassing the end of the nineteenth century and beginning of the twentieth century was marked by a prominent awareness of a need for change in many walks of life in the U.S.A.. This time came to be known as the Progressive Era. In Tennessee, Progressivism featured demands for political and social reforms with curbs on the power of big business. (Mark Twain labeled this era “The Gilded Age” for its excesses.) Simultaneously, there were calls for better highways, improved schools, and the right for women to vote. Integral to the argument for social reforms was the belief that alcohol was most often the source of the problem. This spawned the Temperance Movement, which first took serious shape in the state in the 1870s. In 1877, the Four-mile Liquor Law prohibited saloons within four miles of schools outside incorporated towns in Tennessee. Municipalities were able to modify the law as a local option. Prohibition was on its way, and after 1907, liquor was forbidden everywhere in the state except in Nashville, Memphis, Chattanooga and LaFollette. It was, nevertheless, widely available in illicit bars or from moonshiners. Prohibition remained a bitterly contentious issue until 1919, when the Eighteenth Amendment banned alcohol throughout the country. Even during prohibition alcohol continued to be a divisive factor in Tennessee politics.

This period of Progressivism helped spawn a new generation of politicians, and Austin Peay and Cordell Hull were among them. Both Peay and Hull were destined to play important roles in state, national and even international politics in the twentieth century.

Interest in agricultural issues extended well beyond the Granger Movement of the 1860s and 1870s. The Farmers’ Alliance was a good example. Its members were concerned with market prices, railroad shipping rates and tariffs that supported American industries but made consumer goods more expensive. Farmers stood together and advocated for better prices for farm products, railroad regulations, and easier credit using crops as collateral. Through this process, Tennesseans became ever more engaged in the economics and politics of the “Gilded Age.” Some of the excesses were curbed by the Sherman Anti-trust Act of 1890. Other developments such as the Interstate Commerce Act, expanded river transport. Additionally, the introduction of electric power and the telephone drew Tennessee ever more into the national picture. The beginning of the automobile age and air travel further added to the integration of the state and nation at the start of what would become known as the “American century.”

References:

Bergeron, Paul H., Stephen V. Ash and Jeanette Keith. Tennesseans and their History. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee. 2007.

Van West, Carroll, Ed.-in-Chief. The Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Nashville: Tennessee Historical Society, Rutledge Hill Press. 1998.

Winn, Thomas Howard. “Time-line-1780-1984 U.S. –- Tennessee—Clarksville—Montgomery County.” Clarksville: Austin Peay State University, Working Document. 1984.